Renowned Rambling Romantics

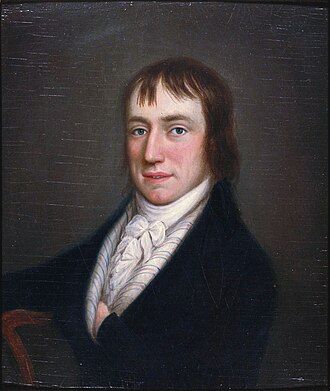

William Wordsworth

A Rambling Genius!

Wordsworth certainly wrote appealingly and expertly about daffodils, mountains, lakes, trees, clouds, winds of various strengths, the rural poor, beggars, idiots and so on. Yet to me, his lasting great contribution to our literature lies not in his skill as a verbal landscape or portrait'painter' - nor even as a recorder of the effects of the Napoleonic Wars and the advance of industrialization, moving and historically relevant though these poems surely are. No ... Wordsworth’s lasting relevance and power lies in his deliberately rambling, discursive approach to poetry and, indeed, to his own thought-processes and memory.

Almost everybody knows I wandered lonely as a cloud and also that he said his wife wrote what he, himself, thought ‘the best lines’:

'They flash upon the inward eye/ which is the bliss of solitude'

Yet this deservedly famous and well-loved poem (usually, in its 1815 version with the added second stanza) does not actually help us to appreciate the revolutionary profundity of Wordsworth’s achievements - for this we need to make the necessary effort to tackle his major work The Prelude.

Although there is still scholarly speculation as to the exact chronology, we can assume that Wordsworth’s plan to construct this poem charting the ‘growth of a poet’s mind’ was conceived, probably at the suggestion of his friend, Coleridge, to whom his poem is addressed, around 1799. This would mean that William was approaching thirty years of age when he started on his epic task:

'The earth is all before me. With a heart

Joyous, nor scared at its own liberty,

I look about; and should the guide I chuse

Be nothing better than a wandering cloud,

I cannot miss my way...

...whither shall I turn,

By road or pathway, or through open field,

Or shall a twig or any floating thing

Upon the river, point me out my course?'

The Prelude (1805 edition), Book First., 15-19 & 29 - 32

What follows is not just an autobiography and/or statement of intent in ‘epic’ verse, though it is possibly the best example of both in our canon, but a dynamic and inspirational, justification of the power and healing effect of the imagination as it operates on us and within us and a demonstration of how and why our memories are often as immediate to us as our present experiences.

Paradoxically, ‘The Prelude’, though rich in metaphor and simile (with many echoes of Milton, Shakespeare and others), neither represents nor symbolises its subject. It simply grows into existence with the ‘mind’ of its creator.

Wordsworth repeatedly and obsessively revised his work, and many of his final revisions of this poem were, in my view, not as successful as he intended but, fortunately, the original 1805 text survives!

If you have not yet read any of The Prelude and you need pointers to the ‘best bits’ why not try dipping into Books One to Four?

The 1805 version is available HERE.

My favourite Wordsworth related walk

....................................................................................................................................

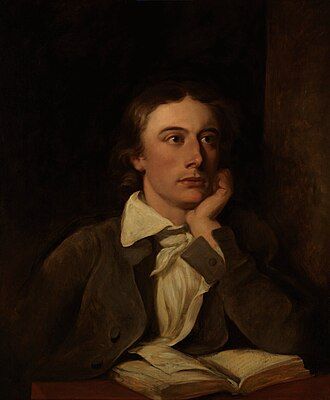

John Keats

Whose name was clearly not 'writ in water'!1

On the 19th September 1819, John Keats decided to abandon his Miltonic epic Hyperion and went for a ramble through the fields on the outskirts of Winchester. We know this from his letter to John Hamilton Reynolds (21st September 1819):

'…How Beautiful the season is now - How fine the air. A temperate sharpness about it. Really, without joking, chaste weather - Dian skies - I never liked stubble fields as much as now - Aye better than the chilly green of spring, Somehow a stubble field looks warm - in the same way pictures look warm - This struck me so much on this Sunday’s walk that I composed upon it.'

The resulting composition, To Autumn, was to become one of the best known poems in our language.

‘Cockney’2 Keats was living in Winchester, having returned from a walking tour in the Lake District and Scotland the previous year, visiting Wordsworth, living in Hampstead long enough to fall passionately in love, meeting Coleridge, visiting Stratford and staying on the Isle of Wight.

He desperately wanted to make his name and his living as a poet but the outlook was somewhat bleak. He had considerable financial problems, was suffering from tuberculosis (from which his much-loved brother, Tom, had quite recently died) and was anxious about his relationship with his girlfriend, Fanny Brawne. Despite all this, his walk inspired him to sit down and construct this near perfect ode. There are so many available critical responses to the poem by those better qualified than I am (and anyway, I’ve written a few too many essays and lesson notes dealing directly or indirectly with it already!) so I will spare the present reader a detailed analysis. These days there are many available on the internet (Wikipedia is as good place to start as any).

Instead, I entreat you first to read the ode (preferably aloud) and enjoy its intensity... then, perhaps, to consider my comment below:

This has been dubbed Keats’s most ‘untroubled’ poem - but tensions between life and death, the settled present and the unsettled future, leisure and labour, thoughts and feelings as well as ripeness and decay, are clearly discernible beneath the technical excellence, luxurious sensuality and warmth of the verse.

A version of the walk Keats took and the text of the poem, are available HERE.

..................................................................................

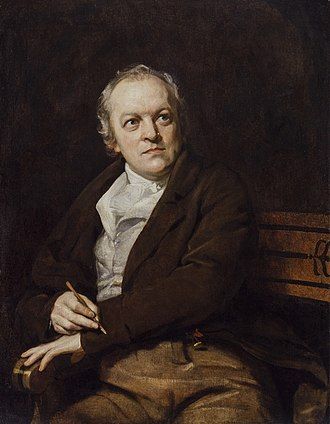

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

An ‘Archangel a little damaged’3

Two of the most celebrated poems of what was eventually known as ' The Romantic Movement’ were written by this extraordinarily complex preacher, journalist, critic, lecturer, metaphysician and rambler who had been writing poetry since his schooldays.

He is, of course, credited with encouraging his friend, Wordsworth, to write The Prelude and it seems he was trying to write a Miltonic epic, on ‘The Origin of Evil’ or something similar, when The Rime of the Ancient Mariner was begun jointly with his friend - their aim being to receive £5 for its publication towards the expense of a walking-tour they were planning together. William, his sister Dorothy and Samuel returned from a walk on the Quantocks on 13th November 1797 and in the evening Coleridge told them his neighbour, Mr.Cruikshank, had had a dream about a skeleton ship and crew. Wordsworth came up with the shooting of the albatross and the possibility of the dead crew navigating the skeleton craft. The two poets intended to collaborate on the ballad but Wordsworth soon realised that he could not work in tandem with Coleridge in that form, so Coleridge took on the task himself, perhaps incorporating a few lines that his friend had suggested. The poem which resulted was a strange, haunting blend of gothic sensationalism, parody, sensibility and sheer imaginative power. Ironically, it is the only poem in the Lyrical Ballads which uses the form of a traditional ballad!

Coleridge was rarely in good health and eventually became thoroughly addicted to Laudanum. In the Autumn of 1797, after taking ‘two grains of Opium … to check a dysentery at a Farm House between Porlock & Linton a quarter of a mile from Culbone Church’ he claimed to have composed, ‘in a sort of Reverie’, Kubla Khan. He also famously claimed that this poem' which we now treasure was a mere ‘fragment’ of the original as he was prevented from completing the work which he was transcribing - the remembered ‘dream poem’ - by the interruption of the notorious ‘Person from Porlock’.

Be that as it may, Kubla Khan with its themes of a lost paradise which the Satanic genius attempts to rebuild, the ‘war’ between the imposed structure and the savagery of nature and wildness of desire, the apparent balancing of these opposing elements (a miracle of rare device,/ A sunny pleasure-dome with caves of ice) is a technically exquisite demonstration of what Coleridge could achieve by employing the richness and rhythm of his/our language.

After many readings of Kubla Khan, I have come to see the final stanza as, possibly, Coleridge’s ‘mission statement’.

I believe Coleridge desperately wanted to become the poet who has regained Eden for mankind by building his ’dome in air’ , feeding on the ‘milk of Paradise’ and, like the Greek gods of old, on ‘honey-dew’ - the nectar or ‘death-defeating’ liquid which would ensure his immortality in the canon.

The following links may be useful and interesting to rambling readers and/or admirers of Coleridge:

Coleridge's Tour of the Lake District

The Coleridge Way

Friends of Coleridge

.....................................................................................................................................

John Clare

Northamptonshire’s so -called ‘Peasant Poet’4

‘I live here among the ignorant like a lost man in fact like one whom the rest seemes careless of having anything to do with—they hardly dare talk in my company for fear I should mention them in my writings and I find more pleasure in wandering the fields than in musing among my silent neighbours who are insensible to everything but toiling and talking of it and that to no purpose’ (Letter to John Taylor)

John Clare was most certainly a rambler in every sense but the unfortunate label ‘Peasant Poet’ says more about literary snobbery than the individuality of his talent. Some critics have regarded him as a minor Romantic, others as a ‘nature-poet', some as a lyrically political spokesman for the rural dispossessed. Much of his work was disregarded in his own lifetime - some was not printed until he had been buried at Helpston for almost a century. More than any other English Romantic, his work displays a naturalist’s observational skills combined with a working knowledge of the countryside of Northamptonshire, Cambridgeshire and Rutland.

He was a farm labourer as a child, though he also went to school in the vestry of nearby Glinton Church until he was twelve. The enclosures and attendant changes in farming practice together with advancing industrialization clearly upset him and poverty was a constantly recurring threat - one which was, of course, shared by many of his neighbours. Consequently, he worked as a ploughman, in a pub, as a gardener, enlisted in the militia and took a job at a lime kiln at Pickworth. As the extract from his letters above confirms, he felt detached from his neighbours, who may possibly have regarded what little formal education he had as a barrier. Following the publication of his Poems Descriptive by John Taylor in 1820 (who is perhaps better known as Keats‘ publisher) he was to mix with the literary set in London which included Coleridge. It seems he also felt marginal in this company, as he was not versed in Philosophy or the Classics - ironically, one of the major attractions of his best poetry is the absence of classical allusions and the use of not only Northamptonshire dialect, syntax and grammar, but also his use of a unique idiolect, a practice in which he deliberately indulged (though editors, from Taylor onwards, have persistently and irritatingly ‘corrected’ his work). Clare clearly detested being 'fenced in', whether by imposed enclosures of the land or imposed structures of grammar and spelling.

Much as I admire Wordsworth, I have never accepted that he fully embraced his own declaration of intent to avoid the artificiality of ‘poetic diction’ (‘to bring his language near to the language of men’, as he argued in his Preface to The Lyrical Ballads). A comparison between any of his verse and Clare’s immediately reveals this. In a footnote to his introduction to The Penguin book of English Romantic Verse (1978 reprint, p xxiii) David Wright suggests comparing The Nightingale’s Nest ( Clare) with The Green Linnet (Wordsworth), The Nightingale ( Coleridge) and , of course, Ode to a Nightingale (Keats). We discover ‘Hail to thee!’ in Wordsworth, ‘Farewell, O warbler!’ in Coleridge, ‘Thou was not born for death, Immortal Bird!’ in Keats - but simply ‘Sing on, sweet bird!’ in Clare.

Clare involves his readers throughout the poem, inviting them to share in his discovery of the nest and enjoy his detailed observations and delight ( Hush!, let the wood-gate softly clap …, Hark! There she is as usual …, There! Put that bramble by - /Nay, trample on its branches and get near… ).

I suggest that this immediacy and intimacy of expression is what distinguishes Clare from most other celebrated poets of this period and, unfortunately, made his efforts less fashionable. What he does share with other Romantics is his radical politics - not particularly acceptable, at times, to his patrons or publishers!

I’ve given John Clare more space than those I have so far recommended as, despite an upsurge in interest and appreciation since the 1960s, there remains a tendency to regard him as a curiosity.

The tragic deterioration in his mental health, his epic 80 mile walk home from an asylum in Essex, his eventually more humane treatment in what is now St. Andrews hospital in Northampton and his days spent watching humanity and writing verses in exchange for tobacco in that town are all well documented elsewhere.

The following links should prove useful:

John Clare Society

Poem Hunter- John Clare

Aliwalks: Helpston Circular

John Clare Cottage (includes suggested walks)

Poemist's John Clare Page

.............................................................................................................

William Blake

In order to fully appreciate William Blake’s work, we need to be aware of his religious and political beliefs. His opposition to the ‘Moral Law’ and the established church places him among the Dissenters. William and Catherine Blake seem to have been interested in, and acquainted with a number of the many Dissenting groups and individuals in London. We should also realise that many Dissenters believed that Christ’s crucifixion absolved them from ‘sin’ for ever (provided they continued to believe in this ‘Everlasting Gospel’ - the substitution of personal faith in God’s love for external laws and prohibitions) and that they should be guided by individual conscience alone. For much of my knowledge of this, I am indebted to E.P.Thompson (Witness Against the Beast: William Blake and the Moral Law, C.U.P. 1993).

Of course, it would do Blake an injustice to suggest that his beliefs fitted neatly into anybody else’s code! His ideology and mythology testify to far more subjectivity, complexity and imaginative power.

Blake's untitled poem, now frequently and confusingly given the title Jerusalem5 was originally included in the introduction to his long epic, Milton (in which he claims to receive the spirit of John Milton in his foot and to ‘walk forward to eternity’)

The popularity of And did those feet... since it was set to music by Hubert Parry during The First World War, may mean that the words have become almost too familiar to us - which could result in possible misinterpretation of this highly original and revolutionary poem from an extraordinary artist, engraver, dissenter and visionary.

Blake began writing Milton while living in Felpham, Sussex, having moved temporarily from his native London. From his letters it seems that he and his wife were enchanted by that ‘green and pleasant land’, contrasting as it did with the city:

‘Felpham is a sweet place for study, because it is more spiritual than London. Heaven opens here on all sides her golden gates; her windows are not obstructed by vapours; voices of celestial inhabitants are more distinctly heard, and their forms more distinctly seen; and my cottage is also a shadow of their houses’.

Here, Blake frequently enjoyed rambling along the coast path and bathing in the sea and, as he indicates in the letter, heard and saw its ‘celestial inhabitants’. Some claim And did those feet ... is based on the legend of Christ’s journey to Britain with Joseph of Arimathea (see Wikipedia entry) though Blake was clearly more than capable of creating his own more complex myths. At the end of Milton, for example, he appears to have an apocalyptic vision of Christ who 'wept and walked forth from Felpham’s Vale', so it seems more than likely that his introduction refers to this.

There have been so many speculative close-readings, analyses and attempted explanations of this short but intense poem that I do not propose to add to these - particularly as I’m convinced that no one definitive reading is desirable. Taken in context, the poem is an emotive call for each individual to reject received restrictive ideologies, and for all inspirational artists , the ‘Young Men of the New Age’, to free themselves (by continuing 'the mental fight') from the dualism of the Classicists, Lawmakers and the Established Church, so that a new reality ( i.e Jerusalem), based on the power of liberated imagination can be constructed, not in the past, nor even the future, but in their own time and place.

Did Blake believe, either through experience or instinctively, that it is ideologies that shape reality and not the reverse?

Link to the poem here.

See a detailed walk map here.

Footnotes

1 'Here lies one whose name was writ in water' is inscribed on Keats' gravestone.

2 Keats was included in a derogatory article on 'The Cockney School' in Blackwoods Magazine which was aimed at Leigh Hunt and his associates.

3 Charles Lamb referring to Coleridge in a letter to Wordworth (1816)

4 Clare eventually became widely known as 'Northamptonshire's Peasant Poet'.

He actually wrote a short poem entitled 'Peasant Poet'.