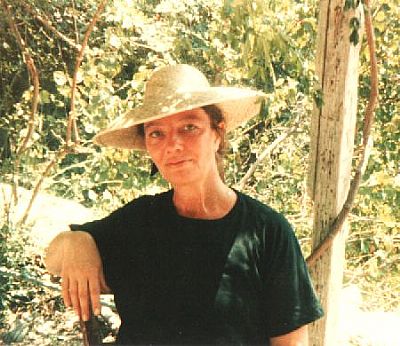

Glenis Hesk 1947-2025

Glenis Hesk MA, BA (Hons), , Cert.Ed

Avid Reader's Previous Ramblings

These pages were contributed by Glenis Hesk, a resident of Cold Ashby, who was, for several years, a part time tutor for Leicester University at their centre in Northampton where she taught courses on the novel. Glenis designed author-based and thematic courses involving not only classic works by nineteenth, early and mid-twentieth century novelists but also fiction by contemporary writers.

Titles commented on below are:

A Perfectly Good Man , This is Paradise,The Sense of an Ending,Birdsong, Pulse, At Last, Birdsong, Gillespie and I, The Outcast, Small Wars, Smut: Two Unseemly Stories, The Stranger’s Child & Wish You Were Here.

A Perfectly Good Man, Patrick Gale’s most recent novel which I found thoroughly engaging and thought-provoking, is set predominantly (though not entirely) in Cornwall and, as always, this author’s skill in conveying a sense of landscape and location is impressive. Similarly commendable is Gale’s ability to gradually peel away the layers of ‘appearance’ thereby exposing the ‘real’ social dynamics which function to shape and ‘drive’ interaction and attitudes in a particular community.

Barnaby Johnson, a seemingly ‘perfectly good man’, is an Anglican priest. Married to the comfortable, practically competent Dot and with two children, Carrie and ‘Jim’, Fr. Barnaby is caring, kind and imbued with integrity but, nevertheless, harbours a secret which he never fully reveals to his wife.

The exploration and unravelling of Barnaby’s personality - what drives him to be as he is, to act as he does - is at the heart of this novel. In the process of ‘explaining’ his central character, Gale interweaves the past and present ‘stories’ not only of Barnaby’s family but also of many other characters involved in his life.

The structure of this novel is both clever and somewhat complex. The narrative unfolds in a non-linear, non-chronological fashion whereby characters are developed and events are revealed in relation to various points in time - each chapter is headed by the name and the age of a character. Into later chapters Gale successfully introduces a few figures who appeared in his previous novel, the much acclaimed Notes from an Exhibition.

To go into details of characters and plot here would be to spoil the pleasure of unravelling the text, though I should mention, perhaps, that there are certain elements which some readers could find difficult - elements which, unfortunately, at some point impinge upon the lives of many.

A Perfectly Good Man is, I would suggest, an interesting novel - an accomplished and near perfectly executed piece of fiction.

..................................................................................................................................................

I have just finished This is Paradise by Will Eaves.

Set mainly in suburban Bath but with brief forays to France, Wales, Cornwall, Dorset and London, this novel charts the progress of the ‘ordinary’ Allden family (parents Emily and Don, and their four children) and their interaction with relatives, neighbours, friends and associates over several decades from the early 1970s onwards. The author’s structural technique involves the depiction of particular situations, episodes and events at various periods in the lives of family members, shifting the narrative forward but leaving lapses of time between sections and chapters.

Eaves writes with skill and sensitivity, displaying a keen eye for detail, a sharp ear for the nuances of conversation, an apt turn of phrase and, at times, a wry sense of humour. Characters are well-realised and the tensions and tribulations associated with family relationships and sibling rivalries, both overt and suppressed, are effectively exposed while affections and empathies are subtly portrayed.

I enjoyed much of this novel and didn’t mind feeling that I must ‘pay attention’ closely in order to ‘keep up’ with and appreciate it fully. The later sections dealing with Emily’s decline into dementia and her eventual death in a care home called Sunnybrook were, however, so poignantly and accurately conveyed that reading became almost unbearable.

Although This is Paradise is interesting, engaging and admirable in many respects, I would suggest that for some, perhaps, reading it may prove to be neither a wholly ‘easy’ nor an entirely comfortable experience.

* Am about to embark upon A Perfectly Good Man, Patrick Gale's most recently published novel and hope that it will prove to be as engaging as his earlier novels, Friendly Fire and Notes from an Exhibition and his short story collection, Gentleman's Relish, each of which I greatly enjoyed.

* Have ordered Bring up the Bodies, Hilary Mantel's first sequel to Wolf Hall.

................................................................................

Have recently finished The Sense of an Ending by Julian Barnes, a slim volume which won the 2011 Man Booker Prize. I found this novel/novella interesting, intriguing, skilfully constructed and written with the precision one associates with this author. Surprisingly, however, I felt that the book was not entirely satisfying.

The narrator, Tony Webster, a man in his sixties, retired, divorced (though on reasonably good terms with his ex-wife, Margaret, and with his married daughter, Susan) recalls and reassesses his past life and present circumstances, dwelling upon and returning to particular relationships and incidents which occurred during his adolescence, his university days and his life thereafter. Of special significance is Webster’s account of schooldays and his friendship with Adrian Finn, a newcomer to his Central London school. The ‘story’ of his relationship with a former girlfriend, Veronica Ford, is also important. Both Adrian and Veronica figure large in Webster’s introspective narrative which periodically reappraises specific events - the suicide of a Sixth-former at his school, a single weekend visit to Veronica’s family home in Chislehurst and a nightime vigil to witness the Severn Boar at Minsterworth.

A small legacy and the bequest of a ‘document’, unaccountably left to Webster by Sarah Ford, Veronica’s mother, four decades after their only encounter, prompts him to contact and eventually meet up with Veronica. The outcome of this ‘reunion’ is uncomfortable for Webster and leads to a further mystery, the solution of which makes some sense of what has gone before but is somehow inadequate.

The book’s title is ‘appropriated’ from Frank Kermode’s literary-theoretical work, The Sense of an Ending (1967), and I wonder to what extent Barnes is playfully testing the reader’s notions of certain aspects of literary theory during the course of his novel. For instance, although Tony Webster seems openly to acknowledge the slippery unreliability of memory, one is drawn to question whether he is himself an ‘unreliable narrator’, or only partially ‘unreliable’, or, perhaps, is reliable but over-introspective and excessively self-obsessed. Also, the circuitous nature of the narrative is, to me, at times reminiscent of Ford Madox Ford’s novel The Good Soldier (1915), a tale told by Dowell, a classic example of the ‘unreliable narrator’ and I am not alone in asking whether Barnes’s use of Ford as Veronica’s surname might not also be something of a literary ‘tease’.

There is much in The Sense of an Ending which is entertaining and engaging (Webster's 'version' of his schoooldays is particularly effective - Barnes creates an impression not unlike that achieved by Alan Bennett in The History Boys) but, upon finishing the book, I felt a sense of something incomplete and inconclusive. It may be, however, that Barnes wrote this novel with a comment by George Eliot in mind. In a letter to her editor John Blackwood in 1857 she remarked:

Conclusions are the weak points of most authors but some of the fault lies in the very nature of a conclusion, which is at best a negation.

...................................................................................................................................................................

Having enjoyed the recent B.B.C. television two-part dramatisation of Sebastian Faulks’s Birdsong, I was prompted to revisit this novel which I first read in 1994, a year after its much acclaimed original publication. My re-reading has certainly proved both engaging and worthwhile.

I had forgotten the precision, the power and the poetry of Faulks’s prose and time had dimmed my memory of his erotic evocation of sexual passion and the chilling impact of his re-creation not only of the nightmare of trench warfare but also of his subtle exposition of the extent to which the realities of the Great War, as experienced by those fighting in Flanders and Normandy, remained opaque to many at home in Britain.

The nuances and enigmatic ‘strangeness’ of the novel’s central character, Stephen Wraysford, his affair with the attractive, unhappily married Isabelle Azaire, his responses to the processes, problems and politics associated with French textile manufacturing during 1910 and his later experiences of disease, destruction and death in the trenches between 1916 and 1918 are all effectively and affectingly conveyed.

Detailed portraits of Wraysford’s comrades, officers and men - Captain Weir, Jack Firebrace and many others - are vividly drawn, being physically, psychologically and emotionally well-realised.

A third element of the novel, involving an account of Elizabeth Benson’s efforts to learn more of the grandfather whom she never knew, is set between 1978 and1979. These shorter sections of Birdsong (Parts 3, 5 & 7) were omitted from the television adaptation and while I would not quibble with the ’cutting and splicing’ of Wraysford’s pre-war and wartime experiences - a film technique which worked successfully, I regretted the omission of the 1978/9 narrative. Not only did its absence necessitate a conclusion which, though powerful and faithful to the penultimate section of the novel, departed from its actual ‘uplifting’ ending but in excluding Elizabeth’s visits to the confused veteran Brennan, ’imprisoned’ in a Star and Garter Home in Southend for sixty years, an opportunity to foreground the plight of maimed and traumatised survivors of war was lost.

For a full appreciation of Birdsong, the text is undoubtedly best.

.....................................................................................................................................................................

Sorry - apologies to those who regularly check out my ‘literary ramblings’ - it has been some time since I added any fresh comments to this page. Rather than laziness, this ‘neglect’ is because apart from Pulse, the most recent collection of short stories by Julian Barnes which , on the whole, I found to be both engaging and poignant, I have been somewhat disappointed in the fiction I have recently encountered.

Having eagerly anticipated Edward St Aubyn’s At Last, I felt that though, as one would expect of this author, it was stylishly written, witty and cleverly constructed, the novel somehow failed to thoroughly engage, at times seeming to verge on the ‘dreary’. At Last, which would appear to be the final ‘episode’ in the author’s tales of the dysfunctional and rather alarming Melrose family, has been much praised by others, however, and so perhaps its funereal aspects and ‘dark’ humour simply didn’t match my mood at the time of reading.

Unfortunately, other novels I’ve looked at recently were so disappointing that I prefer not to mention them here.

Have not yet got round to The Sense of an Ending, Julian Barnes’s Booker Prize- winning novel, but intend to read it shortly. The stories in his Pulse are varied and variable. There are three historical pieces which were interesting but far more engaging were other contemporary stories such as ‘East Wind’, ‘Marriage Lines’, ‘Gardener’s World’ and ‘Pulse’. These, I thought, were not only sensitively written but also achieved a level of ‘connection’ with real and present problems and preoccupations which many encounter day by day. I was somewhat less moved by the four sections, ’At Phil and Joanna’s’. Written in dialogue, these pieces ‘recording’ ongoing dinner-party conversations between a group of comfortably-off, late middle-aged friends reminded me of (and deliberately parodied, perhaps) those Bremner, Bird and Fortune sketches of the metropolitan middle-class milieu ‘at table’ but somehow lacked their satirical sparkle and ‘edginess’. Nevertheless, Pulse is a worthwhile read.

Early last year, purely by chance, I came across two novels by an author of whom I had not previously heard and thought both books rather interesting.

Although neither novel is without a few flaws, I found both The Outcast (2008) and Small Wars (2009) by Sadie Jones most engaging.

Each of these novels is set in the 1950’s and convincingly evokes that post-W. War II period.

The Outcast concerns the past and present problems of a troubled young man, Lewis Aldridge, recently released from prison. This novel gradually reveals the repressions, restrictions and hypocrisy which simultaneously shaped and also often lay concealed beneath the ostensibly ‘respectable’ behaviour of well-off upper/middle-class families during the 1950s.

Small Wars deals not only with the personally problematic husband/wife/ family/professional relationships of an army family posted in Cyprus at the time of the troubles there in the ‘50s but also, and most significantly in relation to current ‘action’ in Afghanistan, with the traumatic experiences of an officer striving to deal with the brutal ( and sometimes brutalising) effects of violent actions towards, and by, the indigenous ‘enemy’.

Both are novels which have been, perhaps, somewhat overlooked by major critics.

Am looking forward to reading Hilary Mantel’s sequels to Wolf Hall. The first, Bring up the Bodies, concerning the demise of Anne Boleyn, will be published in May but I am not sure when The Mirror and the Light, Mantel’s second sequel which will follow Thomas Cromwell’s career up to his execution in 1540, will appear in print.

The ‘Rambler’ himself has only recently got around to reading Wolf Hall (which I reviewed some time ago * see archive) and so I may persuade him to add a comment to this page in the near future.

* Click here for the Rambler's comment!

Have just finished reading Gillespie and I by Jane Harris which I found interesting, intriguing and, at times, a little disturbing.

The 80 year old narrator, Harriet Baxter, a spinster living with a paid companion in Bloomsbury in 1933, decides to write a book about a little known Scottish artist, Ned Gillespie, who in 1892, at the age of 36, had burned most of his paintings and committed suicide. What unfolds, however, is not so much a memoir to the painter as a retrospective account of Harriet’s involvement with Gillespie, his wife, family and friends - an involvement beginning with a chance meeting when Harriet comes to the aid of Gillespie’s formidable mother, Elspeth, and ending in tragedy and a criminal trial.

The main setting is in Glasgow, around and just after the International Exhibition held there in 1888.

Woven into the ‘history’ of Harriet’s past, however, is also a ‘present’ 1933 narrative which discloses details of the current and increasingly worrying circumstances of her life in London.

The account of past events in Glasgow and, later, of the trial in Edinburgh, reads like a Victorian mystery tale and in her adoption of a period-related narrative style which often incorporates a ‘quaint’ vocabulary and her detailed historical references, Jane Harris quite successfully achieves a sense of authenticity. There are in places, perhaps, deliberate echoes of Wilkie Collins and, as in Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw, the question of the narrator’s ‘reliability’ has to be considered. Clues to what may (or may not) follow are subtley scattered, compelling one to continue reading and, though ‘dark’, the novel is not without humour - many ‘barbed’ turns of phrase are most amusing.

On the whole, Gillespie and I is an engaging read, if at times somewhat disconcerting.

......................................................................................................................................................................

Though initially amused by Alan Bennett’s Smut: Two Unseemly Stories, I was ultimately rather disappointed by the book.

Bennett’s acute ear for the nuances and absurdities of seemingly ‘normal’ conversational exchanges between his characters is, as always, entertaining and his eye for the oddities of their apparently ‘ordinary’ behaviour remains keen.

With the unfolding of each of the two stories, however, I sensed that in his selection of ‘unseemly’ subject matter Bennett had set out to shock the reader simply for the the sake of being ‘shocking’ and that his usually engaging mischievousness has turned somewhat sour.

...................................................................................................................................................................

Alan Hollinghurst’s The Line of Beauty won the Booker Prize in 2004 and, earlier this year, many suggested that his latest novel, The Stranger’s Child, might bring its author the award for a second time. This new novel has not made the shortlist, however, and, having read it, I am not entirely surprised.

It is not that the novel is uninteresting, nor does it lack literary merit, complexity or depth - quite the opposite. Certainly, it is very long but this was not a problem for me - I simply found it, at times, rather tedious and feel that more rigorous revisions might have been beneficial.

Having a large cast of characters and a time-scale spanning several decades (each of its five sections is set in particular years - 1913, 1926, 1967, 1979/80 and 2008), The Stranger’s Child concerns the relationships and interactions between members, friends, associates and descendants of two families - the aristocratic Valances of Corley Court and the middle-class Sawles. The initial connection between these two families stems from the friendship, forged at Cambridge, between George Sawle and Cecil Valance, a not particularly good Georgian poet who achieves posthumous fame on the strength of one poem written on a visit to George’s house, ‘Two Acres’, in 1913. The narrative which follows is complicated, involving not only the ‘legacy’ of Cecil’s reputation but also of his behaviour during his visit and afterwards until his death in the Great War. Daphne Sawle, George’s sister, is a pivotal character for much, though not all, of the book.

In a ‘ Bridesheadish’ way, this novel is a cleverly-wrought ‘family saga’, hinting also at elements of Forster’s Howards End, Hartley’s The Go-Between and McEwan’s Atonement. As it unfolds, the novel explores many themes relating to literature, architecture, music, literary journalism and publishing. The ‘feel’ of particular periods/decades is well-realised and there are many descriptive, evocative passages relating to particular environments and houses. The novel documents changes in social behaviour and attitudes. Certain explicitly sexual scenes, however, may discomfort some readers.

In several respects The Stranger’s Child is a terrific achievement on Hollinghurst’s part, but, finally, I was left with the feeling that he had, perhaps, over-egged his elaborately constructed pudding.

........................................................................................................................................................................

Have just finished Graham Swift’s new novel Wish You Were Here which I enjoyed despite its rather sombre content and its intentionally slow pace.

Swift’s realisation of one man’s reactions and responses to a sudden death which precipitates a revisiting of former losses, not only of people but also of animals, land and a way of life, is poignant. Depictions of rural landscapes, weather and seasons are, as always with this author, compelling and evocative.

This is a serious, somewhat circuitous fiction which, as it gradually unfolds, delves deeply into the substance of family relationships, closely examining notions of affection, loyalty, distrust and betrayal.

Prompted by the death in action in Iraq of his estranged younger brother, Tom, the novel’s protagonist, Jack Luxton, confronts experiences which have been suppressed for a decade. The time-scale frame of Wish You Were Here is just one day but the ‘story’ meanders back and forth to cover present, recent and past events in Jack’s life.

Having sold the two ailing family farms in Marleston, Devon on which each had grown up and ‘slaved’ and which each had eventually inherited, Jack and his wife, Ellie, have for many years owned a popular and financially successful caravan site on the Isle of Wight. News of his brother’s death, combined with Ellie’s restrained response and refusal to accompany him to the repatriation ceremony in Oxfordshire and the burial back in Devon, result in Jack’s mental distress and leads to marital discord. Both the pleasures and the hardships of his previous life on Jebb Farm, including the traumas and tragedies incurred as a result of outbreaks of B.S.E. and Foot and Mouth disease, as well as family difficulties, are recalled by Jack as he attempts to deal with his grief.

Though a third-person narrative, events are mainly focalised via Jack’s perspective but not entirely - other characters’ views are sometimes employed. Also, there are occasional hypothetical passages where the omniscient narrator speculates upon what might or might not have occurred or been said at given moments - I found these slightly annoying. Wish You Were Here, with its descriptions of the countryside and the realities of farming, its references to changes in the social structure of rural living over recent decades and its mention of the anonymity of motorways and the ‘urban’, is in part a subtle interrogation of notions of Englishness and an altered England. Allusions to major global events also suggest that into his tale of a man, a family and a farm, Swift has woven slender threads which make his novel a comment upon an altered world.

..................................................................................................................................................................................