Bob Dylan: Songs of Both Innocence and Experience?

Bob Dylan: Songs of Both Innocence and Experience?

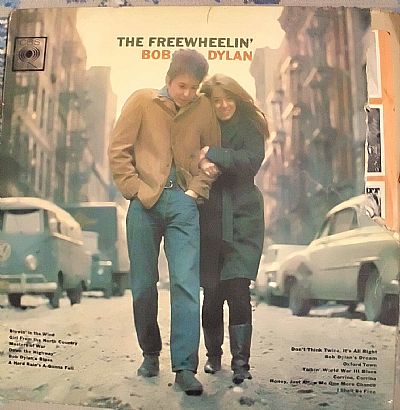

'Anything I can sing I call a song. Anything I can’t sing I call a poem. Anything I can’t sing or anything that’s too long to be a poem, I call a novel’. (Album cover notes, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan CBS 1963) (My treasured, if somewhat battered album is pictured right!)

In 1963 I was not expecting a one time youthful rock & roller turned protest/folk singer to become a Nobel Laureate over half a century later for " having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition"... and it’s reasonable to assume neither was Bob.

I imagine most of us interested in (or indeed studying) music and literature in the 1960s welcomed the simplicity of Dylan's definitions on the album cover of Freewheelin’ - even though we already suspected that Dylan’s work was actually operating on many complex levels simultaneously.

On reflection and with the knowledge of how his writing and performances developed, I think he meant the emphasis to be on what he defined as poetry, song and prose. It’s surely no accident that I occurs six times in the above quote.

That award for ‘Literature’ was probably designed to create controversy and it did – yet the rich tradition of the wandering minstrel, the rambling song and dance man, the performer or sooth-sayer with ‘no direction home’ is central to our understanding and appreciation of innovative poetry and song.

‘I sing of arms and the man...’ writes Virgil at the beginning of The Aeneid and he is borrowing this from Homer who asks his muse to ‘sing’ at the opening of The Iliad.

Homer, in turn, is borrowing from the even more ancient, travelling and singing poets of Greece whose improvised poetic narratives are believed to have been sung to a lyre accompaniment (hence,of course, the terms ‘lyrics’ and ‘lyrical’). These singer/poets performed from memory not from text so we might expect there to be variations, additions and /or omissions between performances plus adjustments made for different audiences and occasions.

Dylan’s work seems to me to be firmly rooted in this tradition – he’s an individualistic, creative public performer who writes and speaks in his own idiolect, expecting his audience to make its own sense of the images his words deliver. He expects us to make a creative effort to interpret what the songs he writes and sings mean to him and to us.

In this, he is operating like the Rambling Romantics of my previous post but in a radically different climate.

When writing poetry and eventually printing it became possible, the traditional connection between song and poetry continued in what was called ‘folk music’.

Fortunately, in the sixties, the so-called ‘Folk Revival’ brought oral poetry and song back where it really belonged and (thanks to advances in recording technology) it has returned to the public domain, while reading written poetry has, most unfortunately, become regarded as more of an ‘academic’ pursuit.

Dylan made traditional ‘Folk Music’ contemporary. He used folk tunes and traditional word patterns to achieve this and got accused of plagiarism for his efforts. He ‘went electric’ and upset the folk music purists ... but their loss was poetry’s gain.

‘Hard Rain’, written during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, borrows the tune and form of ‘Lord Randal’, with its traditional questions and answers, to achieve a chilling dramatization of what could have happened, and ‘Talking World War Three Blues’ in which Dylan, with tongue in cheek, imagines what surviving a nuclear attack might mean to individuals by satirizing the ‘make the best of it’ attitude we are encouraged to adopt to war, loneliness, desperation and existential threat.

I remember vividly the fear of conscription and/or oblivion that surged through me and my mates at school and that song summed it up … and converted me to a life-long Dylan fan!

Sadly, ‘Hard Rain’ and ‘Talking World War Three Blues’ are as chillingly relevant now (November 2024) as they were in the Cold War.

Recommended reading:

Chronicles Volume One (Bob Dylan, Pocket Books 2005)

‘Do You Mr. Jones’ (edited by Neil Corcoran, Chatto & Windus 2002)

No Direction Home (Robert Shelton, Penguin Books 1987)

A Darker Shade of Pale (Wilfred Mellors, Faber & Faber 1984)

....................................................................................................................