Introducing Rosemarkie Man: A Pictish Period Cave Burial on the Black Isle

by James McComas (originally published February 2017)

The Pictish period skeletal remains, c . 430 - 630 AD, of a robust young man with severe cranial and facial injuries was found by archaeologists in a cave on the Black Isle in 2016. As has been widely reported, a facial reconstruction of the man was later produced by Dame Sue Black and her team at the University of Dundee. This is an account of the story from a digger's perspective.

The Rosemarkie Caves Project (RCP), founded and led by Simon Gunn as a part of NOSAS, has since 2006 investigated the archaeological potential of a range of 19 caves on a 2.5 mile stretch of coast north of Rosemarkie. Activities have included comprehensive surveys, test pitting and fuller excavations (see our earlier blog post for an introduction). In September 2016 it was decided that a full two week excavation would be carried out at "Cave 2B" where previous test pitting results had been revealing some interesting results. Here animal bone and charcoal excavated from depth of over one metre had yielded calibrated radio carbon dates of 600 - 770 AD, which is generally regarded as the Pictish period in Scotland. In addition this particular cave also had an unusual built wall structure spanning its entrance. It was felt by the RCP Committee that these factors made it a prime site for more detailed excavation.

Above: View of the cave towards of end of the 2016 excavation. The excavation area had now been divided into quadrants. Note the substantial wall in the entrance.

The Rosemarkie Caves Project was extremely fortunate to have experienced professional archaeologist Steve Birch volunteer to direct the excavation full time. In addition Mary Peteranna was also in attendance on a number of days when her duties as Operations Manager at AOC Archaeology would allow. I had signed up as a volunteer for almost the full term along with the rest of a small but enthusiastic team. What was meant to be the final day of the dig started like any other. We had already had a successful two weeks, having identified a potentially important iron working site. That morning I was hoping to be able take out a section in the wall entrance in pursuit of a possible slot feature there. However I was somewhat disappointed to be deployed in the NW quadrant at the back of the cave, where a cobbled surface had previously been removed and a depth of midden material still remained to be worked back.

Above: Area of laid cobbles in the North East quadrant dating to c. 19th C. Little did we know at the time what was beneath!

Above: Volunteers Robin and Janet Witheridge digging in the North West quadrant.

The area had already yielded one piece of medieval pottery and was continuing to throw up significant quantities of butchered animal bone. This was a part of the cave where light from the entrance barely reached, so hand and head torches were needed to see what we were digging properly. As I continued to trowel down conditions became drier and sandier and it felt as if I might be getting close to "the natural". I now began to find a few beautifully preserved small bones, which I took to be the phalanges of a fairly large mammal. I remember thinking "they could almost be human. What if they were?" However I quickly dismissed these as idle thoughts borne of over enthusiasm. As the day progressed I uncovered the crown of a large boulder plus the tops of larger bones to either side. It was at this point I really began to think we had something interesting here and I remember discussing it with the rest of the team. Deer bones were initially suggested as one possibility, but as the sand was carefully peeled back and more was revealed it soon became apparent that this could only be one thing - human remains!

Above: The large boulder between the legs of Rosemarkie Man, perhaps designed to "hold him down" in his grave.

This diagnosis became ever more compelling as smaller in situ bones began to appear amidst the larger ones. A careful analysis of the finds tray revealed also what looked very much like two patellas, indicating that these were indeed a pair of knees sticking up out of the sand. Excitement levels were now building steadily among our small merry band; this was certainly more than any of us had expected. We also knew that the police would need to be informed of our discovery. At that point none of our contexts were dated, but due to the depth we were now working at we were pretty confident these remains were not remotely recent. We also knew that earlier test pitting results from approximately this level in other parts of the cave had given early medieval dates. At this point I was fully expecting Steve or Mary to take over excavation of the body, indeed I would not have held it against them if they had. However I am extremely grateful that I was given the opportunity to continue for the rest of the day. Needless to say for an amateur archaeologist this was a rare opportunity! It was decided the boulder would have to be moved in order to continue, so with great care Steve and I carried it to the spoil heap. That afternoon saw a couple more painstaking manoeuvres, where some largish stones had to moved from around the periphery without disturbing the bones. Under Mary's expert tutelage I had now abandoned the trowel largely in favour of finger tips, but it was still tricky removing material without moving the smaller bones. The sequence of pictures below pretty well shows how the excavation progressed that afternoon.

Above: Boulder from between legs now removed and smaller in situ bones beginning to appear.

Above: A later stage in excavation, with parts of right arm, left hand and pelvis now uncovered.

Above: The extent of excavation at the end of the discovery day. Note the group of butchered animal bone on a raised section above the skull area and another smaller group above the right shoulder.

At the end of the day much of the skeleton was uncovered and it appeared to be largely complete. However the skull was still covered by a deposit of butchered animal bone on a small island of sand. Due its possible significance to the burial, this deposit needed to be properly recorded before it could be removed. The remains were covered with a tarpaulin to await the arrival of the police. Unfortunately for me this was the last day I had scheduled for digging and normal working life now threatened to resume. Consequently I was offsite the next morning whilst Steve managed to convince the constabulary that the remains were definitely historic and not the result of some recent skulduggery. Nevertheless the Procurator Fiscal still had to be informed, and this would in turn lead to the involvement of the Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification in Dundee - a crucial later development in the story. Meanwhile, I could not resist juggling my schedule around to come back in the afternoon to see how things were progressing. As my wife put it "you've got to go back, you may never get a chance like this again!" I arrived to find the police long gone and Steve busily finishing off excavation on the skull. I remember being initially slightly disappointed at the condition of the skull with all its fractures compared to the remainder of body. However at the time we did not realise what a gruesome and compelling story these fractures would tell.

Whilst Steve continued work on the body, I helped out by half sectioning some post hole features. Later, whilst Steve planned elsewhere, I used my tripod to take a range of photographs of the skeleton from all angles, hoping they would produce some good photogrammetry results. I had previously done the same with the built wall at the front of the cave (see below), but here tucked away in an alcove at the back, light conditions were considerably worse. I did not wish to risk distorting the results by using flash, so lengthy exposures were needed to get anything usable. RCP veteran Bob Jones was also on hand with his camera, so in the end I combined some of his pictures with mine to build a 3D model.

Above: Three views of the photogrammetry 3D model. Below: The model itself. The results are not as clear as I would have liked, but due to the significance of the find I include them anyway.

I left that evening with the remains of Rosemarkie Man still in situ. Steve would return yet again the following morning to finish off on site and lift the bones. There was still a possibility that there might be grave goods or further deposits beneath the bones, but in the event this proved not to be the case. Despite very careful excavation and sieving of spoil, only the bare skeleton was found. This led to some conjecture that he may have been partially or wholly naked when buried. During the ensuing weeks, the Rosemarkie Caves Project Committee kept up a steady a stream of detailed email correspondence. This was principally from Steve to tell the rest of us what was happening with the bones and other finds. Here we had the enormous good fortune of having Dame Sue Black at the University of Dundee agree to handle the skeletal analysis of our man. It was only later I found out that the Procurator Fiscal had contacted Sue Black for a forensic opinion since the skeleton seemed so complete and in such good condition for an historic specimen. Sue, although convinced Rosemarkie Man was not a modern murder victim, was so intrigued by our find that she agreed to take on the full analysis as a teaching vehicle for her students. Indeed when she laid out the skeleton it proved be complete aside from a few small bones. As she later put it, "it doesn't get better than this!" It was certainly a relief to me that we had excavated carefully enough to recover so much, even though some of the first bones went straight into a finds tray before we realised that we were dealing with human remains. Rosemarkie Man was probably in his early thirties and powerfully built with particularly well developed upper body muscles. Aside from some rather poor dental hygiene he appears to have been very healthy. The real news however was his skull. Sue confirmed 5 separate severe facial and cranial traumas (I have paraphrased in some parts):

- A penetrating trauma to the right side of mouth where teeth were broken by an implement which was round in cross section. He was certainly still alive following this since one tooth fragment was inhaled and later recovered from beneath the sternum.

- A blow to the left side of jaw, cracking the mandible with great force. This may have been made with the same the same implement, used like a fighting stick at close quarters.

- Contact fractures on the back of the skull that are likely contra coup caused by a fall where the head hit a hard object such as rock. This was probably a direct result of the man being knocked down by injury number two.

- Whilst on the ground an implement, possibly the same one as before, was driven through the side of his head from the left through to the right just in front of the temple region. This was likely the cause of death.

- The top of the skull was penetrated with tremendous force causing massive fracturing. It was made with a different implement to that used previously, creating a larger hole. This injury does not fit in with the pattern of the earlier ones. This final blow could have been the coup de grace or it could have been done after death in ritual - this cannot be confirmed either way.

Above: Two close ups of the skull. Bottom image by Bob Jones.

It is open for conjecture whether the initial attack on the man was carried out by multiple assailants, or whether it was a single attacker with one weapon. The facts, as Sue Black confirmed, could support both hypotheses. There is nothing to say either whether this was the result of interpersonal conflict - more likely if there was single assailant - or if the attack had a sacrificial element. The last injury is interesting in that there might be a suggestion that the skull was fractured to let the spirit out after death, as seen in some Iron Age examples. The level of trauma inflicted, far more than would have been needed to kill him, also raises comparisons with Iron Age bog bodies where high status individuals, who may have been willing or at least compliant, suffered a "multiple" death. These bodies were typically deposited in watery pools where, as Steve pointed out, they were sometimes held down using wooden stakes and hurdles. These deaths are sometimes thought to be sacrifices made to propitiate deities during times of poor harvest. The location of Rosemarkie Man's burial placement, set into an alcove in the back of the cave, plus the unusual positioning of the body with boulders and butchered animal bone placed over the top, may all indicate a particular significance to this individual and to his death. Conjecturally the cave itself may have been regarded as a liminal space at this point, like the watery pools bog bodies were placed in, and the boulder holding him down might have served to ensure he did not return to trouble the community after death.

Above: A “photoshopped” attempt to put the boulder back into position found with the entire skeleton exposed.

The news on our man's injuries was fascinating if grisly, however what really put the tin lid on it was the radiocarbon date which arrived just in time for Christmas. This result was obtained from one of Rosemarkie Man's ribs and was one of two free samples dated through the CARD fund. At 430 - 631 AD it showed that the skeleton dated to the start of activities in the cave, pre-dating or contemporary with the early medieval occupation and metal working horizon (RCP 2016 DSR). The date was a great Christmas present putting Rosemarkie Man in the early to mid Pictish period. Pictish human remains are generally poorly preserved and finding a well preserved and almost complete example like this made the find especially significant. I had some brief correspondence with Dr Adrian Maldonado, an authority on Pictish burials, to ask him about the best examples of Pictish skeletons he was aware of. Adrian told me these were probably the remains found at Portmahomack by Martin Carver, the next best being those from Hallow Hill in Fife. I next contacted Dr Shirley Curtis-Summers who has recently published her analysis of the Portmahomack skeletons. Shirley told me that of 13 skeletons dated c 550 - 700 AD, only 2 are near complete and these are in either poor or fair condition. Rosemarkie Man, as we have already established, is almost complete and in very good condition (for further discussion on early medieval human remains see SCARF Report 4.5.1). The most recent development has of course been the striking facial reconstructions by Dame Sue Black and her team, which serve literally to put flesh on the bones of the story (see versions with and without hair below). Combined isotope analysis is now also being carried out and these results should tell us if the man had local origins or came from further afield. If he is from the highlands we can be more confident about labelling him a Pict. There remains the possibility though that he could be Scandinavian, or from a different part of (what is now) Britain or Europe. Ancient DNA analysis will now also be undertaken, but it remains to be seen whether this will yield any usable data.

Iron Working Samples to be analysed from the dig also included iron working slag and vitrified furnace lining that we had recovered. This material was found close to the suspected remains of a bowl furnace in the South East quadrant of the cave, opposite the body and at a similar level in the stratigraphy. The piece of vitrified furnace lining was later found to have part of a pipe-like hole passing through it. This was half of the tuyere - the hole where a bellow pipe would have passed through the furnace wall to introduce air.

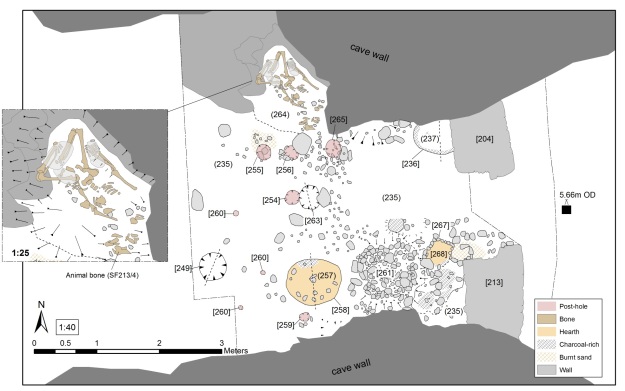

Above: Plan of the metal-working features, post-holes and pits and the inhumation burial in top centre; inset: mid-excavation of the inhumation showing the location of the stone placement over the body (Mary Peteranna). Below: Piece of vitrified furnace lining and the site of the bowl furnace.

Iron working finds analysis by Gemma Cruickshanks of NMS is currently still ongoing. However early conclusions point to the sample material being representative of smithing, rather than smelting. Later radiocarbon dating of a sheep rib excavated from the context immediately covering the metal working horizon gave a broad date of cal AD 718-941. Therefore it seems metal working was almost certainly taking place during the Pictish era, although from the evidence we have it would appear to post date Rosemarkie Man. Dating of other horizons during test pitting suggest that the main period of early medieval occupation in the cave relates to the early 8th century AD. The metal-working industry could be earlier than, or contemporary with, this period (RCP 2016 DSR). A series of post and stake holes in the metal working area may have indicated that the space was enclosed on three sides by screens and the cave wall, leaving only the way through to the cave entrance open. As Steve and Mary argue, "this interpretation, along with the location of some of the post-holes, also suggests the possibility that the burial location was known and respected by the smithing area". It could also be argued that Rosemarkie Man was related to the iron working industry in some way. With his well developed upper body he may even have been a smith himself, and his burial could conceivably have inaugurated the start of smithing in the cave (RCP 2016 DSR).

The Cave Entrance Wall This substantial mortared wall, which would have stood over 1 metre high, likely had a wooden door for which door checks survive. It may also have been surmounted by a screen, increasing the height further. The precise dating of construction remains uncertain but it definitely post dates the early medieval occupation and predates the last 19th C. horizon. In terms of function it may have helped the define and secure the cave as a dwelling, store or animal shelter, but this remains conjectural (RCP 2016 DSR).

Above: The cave entrance wall towards the end of the excavation. The images below are from a photogrammetry 3D model, made up of multiple photographs from different positions.

Above: Outside the cave during lunch break: L to R Allan MacKenzie, Tim Blackie, Simon Gunn, Steve Birch and Mary Peteranna.

References:

Steve Birch and Mary Peteranna - RCP 2016 Data Structure Report (DSR)

Steve Birch - Rosemarkie Caves Excavations: Interpreting the results of three years of excavations – 2016 to 2018

Out of Doors 9.9.17 BBC Radio feature - listen here

Landward 13.10.17 BBC TV - watch here

Many thanks to Steve, Mary and Dame Sue Black who I have all paraphrased liberally in the above article. Thanks and congratulations also to Simon Gunn and the rest of the RCP team on the fantastic results of this excavation, I am fortunate to have been a part of it.

Update 2019: In July 2019 Rosemarkie Man hit the news again when the story was updated to reflect what we had learnt from the currently unpublished isotope analysis results. This led to speculation in the media that our man may have belonged to "Pictish royalty" (see for example BBC News). The isotope analysis found that the source of protein in the diet of Rosemarkie Man was different to contemporary Pictish populations from elsewhere in Scotland. This may have included freshwater fish, water fowl, or higher-trophic level terrestrial fauna such as suckling (young) pigs. A similar, elevated value was found in a male from a high-status burial at the Pictish site of Lundin Links. This doesn't prove Rosemarkie Man was Pictish royalty , but it's certainly a theory that he may have been of high status. We also ascertained that he most likely originated in the local area. The results of Rosemarke Man's DNA analysis can be seen here.

Update 2023: A new TV documentary, Ancient Murders Unearthed: Rosemarkie Man, was first shown 19.06.23 on Sky History. It was released on CuriosityStream in the USA. The programme was filmed in February 2022 at Rosemarkie and other locations - it features interviews with the author, Steve Birch, Sue Black, Gordon Noble and Kate Britton amongst others, and aims to solve who killed Rosemarkie Man. It can be watched on NOW TV here (subscription required).

Meanwhile, in October 2023, podcaster Michael Holm also made a programme on Rosemarkie Man. Michael, who had originally grown up at nearby Hillockhead, interviewed the author along with Bob and Rosemary Jones in Cave 2B. The programme, Brutal UNSOLVED Pictish Murder | Scottish Archaeology | The Rosemarkie Caves was released on YouTube, Itunes and Spotify in November 2023 (watch below).